Have you ever become involved in something so far beyond your skills or ability that you can see no way out of it? Something that at the time of starting seemed like a great idea or a funny story for later – like starting a marathon in flip flops or becoming president despite any political experience – but that after less than two minutes reveals itself to be a horrible, tragic mistake.

For me, my mistake was marzipan. More specifically, it was attempting to build a replica of old St Paul’s cathedral out of marzipan using a 17th century recipe on a Saturday night. Don’t tell me I don’t know how to have fun at the weekend.

Let me explain. I’d been flicking through Terry Breverton’s The Tudor Kitchen and had been really intrigued by a whole chapter on Tudor sweets and banqueting. During the 16th and 17th centuries, banqueting guests would enjoy a feast of predominately savoury dishes served all together. After enjoying this meal of many dishes and side dishes, they would then move to another room where a second meal – the banquet – waited for them made up exclusively of sweets, candied fruit and nuts, and sugar plate. The intention of the sugar banquet was to delight guests with sweet treats disguised as other things, such as gloves made out of sugar paste (no, I don’t know why), as well as impressing them with the variety and expensiveness of the sugar and spices laid out. In fact, a clue that banquets were more about showing off than about actually enjoying the food is in the word itself; we get the word banquet from bancetto, Italian for bench, because the sweets served at a banquet would be laid out on a long table to make it easier for guests to view.

In the Tudor and Stuart mind, no banquet was complete with marzipan.

Gervase Markham, whose recipe for marchpane inspired today’s experiment, wrote in his 1615 work The English Huswife that marchpane – stiffened marzipan – should have “the first place, the middle place, and the last place” of a banquet, which highlights how important the stuff was to Tudor and Stuart feasting.

I was intrigued; my experience of marzipan was that it was a necessity in order to make fruit cakes marginally more edible. Sure, it was nice enough at Christmas but was it good enough to serve in great blocks during feasts? I remembered asking my mum for a cake shaped like a hotdog and covered in coloured marzipan for a BBQ birthday party, but even the memory of this highly sophisticated cake left me unconvinced that I’d want it three times during the same meal.

A little bit more research told me that Tudor marchpane was a very different creation to modern day marzipan, in terms of usage. Whereas modern marzipan is often hidden under thick sheets of painfully sweet icing, the Tudors made it a centrepiece of the meal by carving it into elaborate shapes and covered it in nothing but a bit of gilding, if it could be afforded. Occasionally it would be dyed with natural dyes like parsley or sandalwood, but its main function was to be edible table decoration; Markham wasn’t serving blocks of plain marzipan to expectant guests at all. I suddenly wished I could go back in time to 11 year old me as she explained to her friends why a marzipan hotdog cake was better than a ‘Colin the Caterpillar’ cake and tell her not to worry; in requesting a marzipan sculpture as my birthday centrepiece I was actually celebrating a longstanding tradition and not just being “a bit of a weirdo” as my sister put it.

Other than hotdogs, what other things can marzipan be shaped like?

Elizabeth I was certainly one Tudor monarch who would have appreciated the marchpane hotdog. Long famed for her sweet tooth, a German traveller commented that Elizabeth’s teeth were black which was a “defect the English seem subject to, from their too great use of sugar.” When she died at the age of 69 years old, it was reported that she had lost most of these rotten teeth.

One of the many sweet foods that Elizabeth was partial to was marzipan. And marzipan shaped like famous buildings was considered the height of fashion. At some point in her reign the Queen had been presented with a gift of a marzipan replica of St Paul’s Cathedral. It was likely that such a creation, in all its intricacies, would have required a team of expert cooks and taken years of practice to master. In my overambitious and egotistical way I attempted to recreate it in one evening, in my tiny kitchen, having had no confectionery training whatsoever. What could go wrong? Well pretty much everything, it turned out.

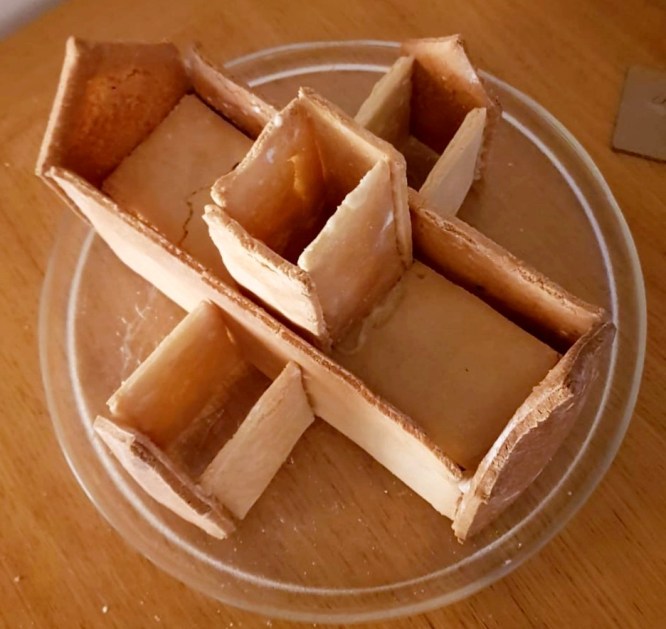

In lieu of a team of expert cooks I roped my husband into holding up walls while the sugar syrup cement dried. He also had to act as a scapegoat for anything that went wrong (he later told me it was the most fraught and unpleasant evening of our married life), and provide soothing glasses of gin before crucial moments during the construction. When it inevitably all collapsed after several hours’ work and my husband pointedly asked if this was what I’d truly meant when I’d told him I had an “exciting Saturday night project planned for the both of us”, I decided to switch tack.

In 1562 Elizabeth received a New Year’s gift from her master cook, George Webster, of a “faire marchpane being a chessboard”. This seemed a lot more manageable, mainly because chessboards tend to be flatter than cathedrals, so once the dust had settled I tentatively told my husband that I’d be attempting a second marzipan creation again in the morning.

As he preemptively booked us for marriage counselling, I got to work. Markham’s recipe was very simple, with an emphasis on the quality of ingredients used, not the quantity. All I needed was ground almonds (Markham advised using Jordan almonds and grinding them to a pulp, but Sainsbury’s didn’t offer me that much choice), very finely sifted sugar (I used icing sugar to achieve the levels of fineness needed) and rose water.

I combined the almonds and sugar in equal quantities – 400g of each – and added two teaspoons of rose water. Then, kneading as if it were a bread dough, I began to work the mixture together, adding a little water to help it stick, until I had a stiff and cohesive block of marzipan.

I was then faced with a dilemma: what colour the dough should be. Despite our modern images of them, chess boards weren’t always white and black – quite often they would be white and any other darker colour, most often red. The important thing was to get a deep contrast between a light colour and a darker one.

A 1534 inventory of the belongings of Catherine of Aragon recorded that she possessed “two chess sets, with red and white chessmen.” I don’t know how Elizabeth would have felt about the use of her father’s first wife as inspiration for my marzipan chess set (especially given that Catherine never accepted Henry’s marriage to Elizabeth’s mother, Anne Boleyn), but by the time I’d really thought about it, half the marzipan had been soaked in beetroot juice so it was too late to get hung up on whether or not Elizabeth would have appreciated this detail.

First up to be made was the chessboard.

I cut out 64 individual 3cm by 3cm squares – 32 red and 32 white. It took forever and I began to panic that I was embarking on another Cathedral Palaver. I considered employing an expert team of cooks, such as George Webster would have used, but one half of my team had barricaded himself in the bedroom and refused to come out until this attempt was over and the other half just wanted to lick icing sugar off everything. Nevertheless, I continued on and arranged the squares like a chessboard before cutting out a border. To make the marzipan stiff I baked it in a low oven for half an hour or so.

As the board baked I started on the figurines. This was by far the most fiddly and annoying bit. In my head they were beautiful elegant carvings with crisp lines and sharp edged. In reality each one ended up as a nondescript, blobby mess. I must have practiced the knights eighteen times before they stopped looking like deformed hippos and began to resemble at least something related to horses.

It didn’t help that the beetroot juice had made the red dough more sticky. Every bit stuck to my fingers and each piece was pulled slightly out of shape each time I tried to set it down. I wasn’t basing my pieces on any particular set because it was surprisingly difficult to find pictures of Tudor chess sets online. All I could find was paintings from the time which indicated that the pieces looked broadly similar to modern day sets so that’s what I aimed for.

I put the figurines in the oven and began to decorate the chessboard, which had been cooling for a while. During the baking process it had puffed up a bit, a little like pastry, but once cooled it had flattened out a little.

It’s likely Elizabeth’s chessboard would have been decorated with gold leaf to give a red and gold contrast that highlighted her wealth and luxury. I didn’t have any gold leaf and even if I had I’d never be able to afford enough to cover each square properly. What I did have, however, was edible gold metallic paint leftover from a birthday cake I made last month. It wasn’t as elegant as gold leaf but it did the same job and soon my chessboard gleamed regally.

At this point, as I was basking in the glory of my chessboard, my husband informed me that the figures in the oven had melted.

As I sprinted to the oven I wondered whether George Webster died from stress brought on by the highs and lows of creating marzipan nonsenses like this? I don’t know, but if my own experience is accurate, it’s very likely. I felt my blood pressure rising as I peeked into the oven and saw that the figures were well and truly ruined. With a heavy heart, I remade them, hippo-horses and all. Instead of putting them in the oven this time, though, I stuck them in my very un-Tudor fridge to firm them up a bit.

Once they were a bit firmer and the horses were less…droopy, it was time to daub them in their own gold paint and arrange them on the board to see how they whole thing came together. It didn’t look too bad!

True, some of the proportions of the pieces were a bit off, and there were some definite lumps and bumps that I doubt would have made the cut on Elizabeth’s board, but overall I was quite happy with it. I could definitely see how something like this could be worthy of being a centrepiece at a banquet. Yes, part of me still wanted to have a glorious 3D model of St Paul’s Cathedral as my showstopper, but the chessboard was a decent alternative.

In terms of taste it was less sweet than modern marzipan is and much nuttier, possibly because the baking had enhanced some of the almond flavour. It was also much more fragrant than modern marzipan thanks to the rosewater in it. The two flavours combined – almond and rose – made a very pleasant pairing with neither overpowering the other.

The texture of the marzipan was also different to what I was used to. There was no limpness to it at all – it was like a well baked biscuit. It cracked and broke easily so had to be handled with care, but was surprisingly light once baked, a bit like meringue. I actually preferred it to modern marzipan.

So after all this what was the chessboard the centrepiece for? Some fancy Tudor inspired meal? A homecooked feast? No. After all the time and effort, all the stress and tears, all the endless wiping sugar off the kitchen table and trying to stop my daughter licking every worksurface, the great marchpane chessboard ended up being the centrepiece for…a Chinese takeaway.

Perfection.

E x

Marchpane

300g ground almonds

300g icing sugar

1 teaspoon of rose water

- Combine all the ingredients together in a large bowl.

- Knead it all into a dough using your hands. Add a little water, drop by drop, if needed.

- Roll the marchpane out into what ever shape you want no thicker than 0.5cm.

- Place on a baking tray sprinkled with icing sugar or covered with a non-stick sheet and bake at 120 degrees c for 30 minutes, or until the marchpane is just starting to colour at the edges.

Your chessboard is heaven on a banquet table. Fascinating history — can’t quite get Elizabeth’s black teeth out of my head — and definite deliciousness.

It was pretty amazing when it was done, not sure photos did it full justice. Bit of a cheat one though, more about the design and look of the thing rather than proper historical cooking (didn’t use bottles and bottles of rose water, for example!) But it was delicious either way. I love marzipan.

Instead of chess – next time make a checker board! Or cut thin flat silhouettes of the chess pieces and stick them in a disk with a groove across the center. – egg white for gluemaybe

Ooh a great idea! Thank you.

Grandmother of a friend of mine used to dip her fingertips in rosewater when making marzipan shapes to keep the stickiness under control. She would also sometimes use orange blossom water instead.

That’s a great idea. Think I’d prefer orange blossom water out of the two.

Great centrepiece! Info: Jordan almonds are sweet almonds opposed to bitter almonds! The Tudors were crazy about both and happily ignorant of the cyanide in the latter!

This was quite an entertaining read. I’ve never tried baking marzipan, but I make marzipan fruit on a semi-regular basis for gift baskets and reception tables in the SCA. I just let the stuff air out to dry and then keep the excess in a ziplock bag in the fridge. Admittedly I use a modern recipe these days, but when I started out I made a boar’s head out of 18 POUNDS of marzipan for a 12th Night celebration (and god help me I listened when someone made the suggestion that it should wink — my husband made the eyes and one eyelid out of hard crack candy). It was a complete mess because I’d never used paste food coloring before, and was just sort of brushing it on with my fingers (people kept telling me my lip was bleeding; and big burly fighter-types were going up to him — trying to coordinate a major feast with multiple courses AND multiple price points — going “Everything all RIGHT at home?” in a menacing fashion). The guy who was supposed to present it to high table didn’t bother to tell anyone (including his girlfriend at the time) that he had to leave to go to work. The guy coordinating the servers was allergic to dairy, and had gotten into some somewhere earlier while making a shopping run for his mom, who was running the event and half the kitchen crew were drawing straws as to who got dibs to stab him…. But we got a replacement to present the boar’s head, and it winked at the Princess, who jumped back about two feet! And then years later walked up to me and said “Was I hallucinating that night?” “Nope — it really DID wink at you….” And I managed to NOT burn out the motor in our original (smallish) food processor, which had been a wedding present for my mother-in-law, by only doing a 1 pound batch of the stuff at a time.