A couple of weeks ago I got a gift. And, to pinch a Tim Minchin lyric, “like most gifts you get it was a book.” Actually, it was several books (and for any Minchin fans who were wondering – no, none of them were the Bible.)

My gift was a bundle of retro cookbooks from Lyalls Book Shop containing such gems as Dainty Dishes and Cyril Scott’s Crude Black Molasses: The Natural “Wonder-Food” – a pamphlet dedicated to promoting black molasses as an alternative medicine for almost all injuries and illnesses known to man. Scott, a composer and musician, also published other ‘medical’ works including Victory Over Cancer Without Radium or Surgery. This publication gave Scott a chance to flex his medical credentials as a “musical composer with a taste for philosophy and therapeutics”, which must have come as a blessed relief to the doctors of the time who Scott describes as being knowledgeable but “not necessarily wise or even skilful” and who had become “so cluttered up with accumulations of academic learning” they could therefore no longer see the simple and obvious facts surrounding the causes and treatments of cancer. He sold himself as a layperson who, unlike medics with “professional prejudices” (you know, like using cutting edge science to treat people), was blissfully unburdened with any medical training whatsoever and was therefore perfectly positioned to advise the public on the kinds of cancer treatment available to them – the more molasses involved, the better. An unfortunately prolific writer, Scott also published other works such as The Art of Making a Perfect Husband (actually I might get that one) and a 1956 opus magnum entitled Constipation and Commonsense.

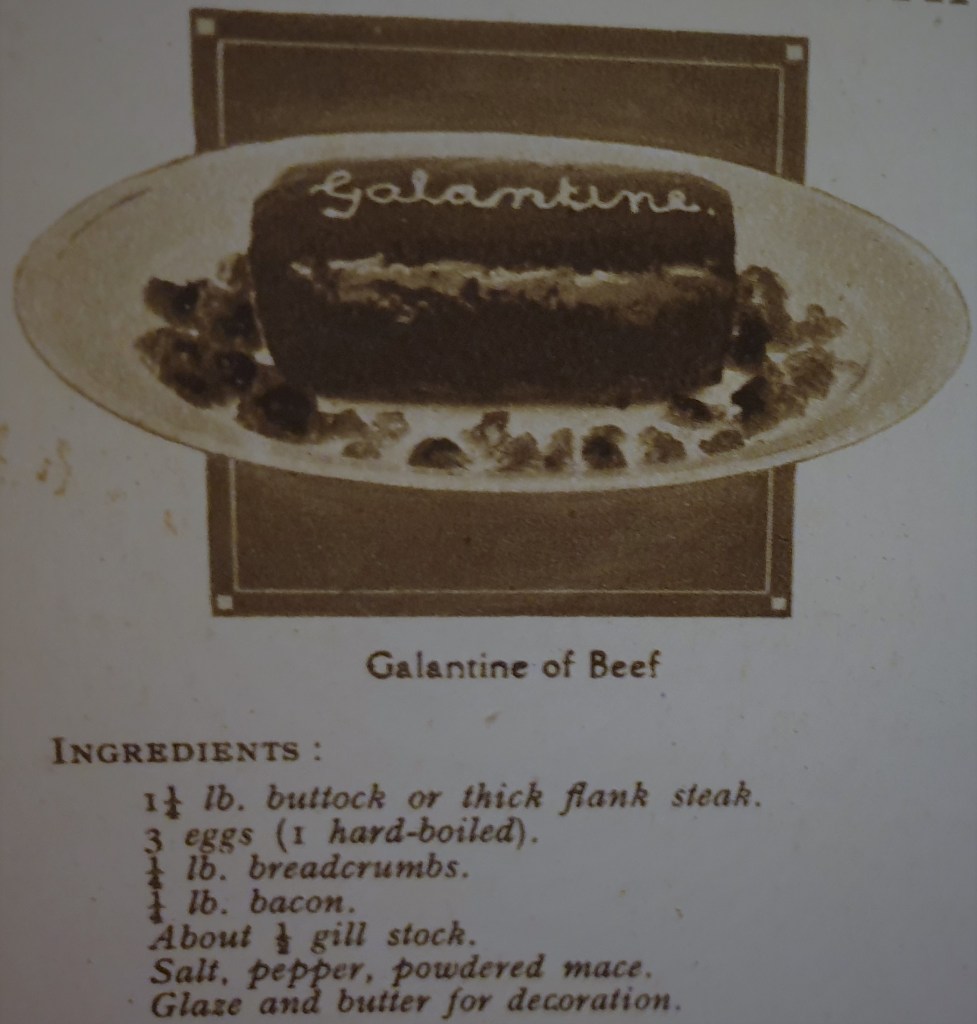

But among the comedy was a Bestway Cookery Gift Book that promised to take me “step by step through the Everyday Dishes to Delightful Experiments in high class Cookery!” I couldn’t find too much info about the Bestway series (my book was a fourth book) but it seems that the offices of the “Best Way” series published a yearly book of recipes during the 20s and 30s for housewives. The books covering a range of recipes ranging from simple household staples like sandwich cakes to more challenging dishes such as Galantine of Beef (an inexcusable serving suggestion implied this dish should be served with the word ‘galantine’ piped over it in butter forced through an icing bag.)

The Bestway Cookery Gift Book was pretty functional and contained very few tips and tricks about its recipes – unlike modern cookbooks that are 30% anecdotes about how the author’s treasured and very secret family recipes were passed down faithfully through the generations only to end up reprinted in six languages.

The closest I could find by way of an introduction to today’s recipe was a paragraph called “Jam-Making Hints” which was confusingly formatted like an acrostic so that I spent a disproportionate amount of time trying to work out how to pronounce ‘UANKT BWP’ and what it meant. It actually turned out that each point was meant to be an easily remembered tip in jam making, like the world’s most impossible mnemonic; so far I just have Underdressed Androids Never Kick The Ball Without Permission which, I found out, was not a helpful jam making tip in the slightest.

Anyway, on to the jam. Straight away it was a farce. When doing these sorts of experiments I like to aim for as much authenticity as I possibly can and I start with a score of 100 and mentally deduct points for every alteration or mistake I make. Usually I end up with around 70 points left over but today I’m proud to announce I hit a new personal best: 40.

“4lbs marrow” was the first ingredient. Nowhere was selling marrows but I did have three large courgettes in. A quick Google told me that marrows were basically courgettes that had been allowed to go over (sort of) so I figured there wouldn’t be too much harm in using these instead. Minus 20 points for substitute ingredient.

I also didn’t have 4lbs of them so I had to half the recipe. Later I’d find out that this was a good thing, but at the time it felt like I was tipping further into the void and I deducted another five points. Once the ‘marrows’ had been peeled and chopped I saw I was supposed to pass them through a mincer, which we didn’t have. What we did have, though, was a blender which achieved a perhaps slightly too mushy result, but was infinitely quicker than trying to chop the courgettes by hand into mincemeat (or should that be minceveg?). Minus a further 10 points.

The recipe then instructed me to put my minced marrow into a bowl and “sprinkle with sugar and leave overnight.” So just how much sugar should I sprinkle on? Why, just over 1kg of course. It wasn’t so much a sprinkling as an avalanche but I was 35 points down already and had already seen that the words “preserving pan” appeared in later instructions (I don’t have one) so couldn’t afford to fritter away any more points. I delicately dumped sprinkled an entire bag of sugar over the courgette mess and left it overnight.

Despite the recipe recommending I return to complete the next stages “in the morning”, I actually forgot it was there until the next afternoon by which time the mixture was exceptionally stiff, almost like fondant icing, and a very faint green colour. The next stage was to add 1 large tin of pineapple, minced, to the courgette and sugar mixture. Ever so helpfully the recipe gave no indication how large “1 large tin” actually was.

At this point in the day there was a big government announcement about an advisor who had broken lockdown rules but wouldn’t be punished for it. I was therefore a bit distracted when adding my pineapple which explains why I accidentally forgot to half the amount to match the courgette and sugar, and estimated that 1 large tin was about the size of 2 small ones (which was what we had in) and added those, blended, to the mixture. Minus 15 points for incorrect quantities and over blending of pineapple, resulting in lumpy juice rather than finely minced fruit (but plus 100 for being able to stick to lockdown guidelines for 10 weeks even when those in charge can’t, am I right?)

It was now time to heat everything in my non-existent preserving pan. There seemed to be an awful lot of mixture and I doubted whether it would all fit in any of my saucepans so I chose to cook the jam in my ever reliable and ever inauthentic wok, which I’ve used to help Anglo-Saxon and ancient Persian bread rise, but have never actually used to cook a stir fry in. Yes, yes I know – minus 10 points. The trouble with cooking jam in a wok, I found, was that it didn’t heat evenly. I knew I was trying to get to about 105 degrees C for it to set, but after 15 minutes or so some parts of the wok were nearing 105 degrees and others were struggling to get past 100. I decided to transfer half of the mixture to a pan and cook it in batches, which worked much better.

After skimming off the scum and adding the juice and rind of a lemon, it was time to take the mixture off the heat. It looked pretty dubious. I don’t know a lot about jam, but I do know it relies on pectin to make it set, which is mostly present in the skins of fruits, particularly hard fruits. Not only had I used two very soft fruits, but I’d also peeled them thoroughly beforehand. The majority of the pectin was therefore coming from one measly lemon which, I now noticed, had a used by date of May 16th. I don’t know if that affected the levels of pectin in it, but with the way this whole thing was going it felt like this would only be a bad thing. I wasn’t sure my jam would set as firmly as I was used to but short of actually following the recipe properly by using the correct ingredients, quantities and methods, I felt I’d done all I could.

Amazingly, one thing I had done properly was sterilise some jars to put my jam in. The trouble was that both jars were old pickled onion jars and had retained some of their vinegar-y smell despite my best hot water and soap efforts. In a last minute attempt to find jars that didn’t have such an offensive whiff about them I raided my fridge for almost empty or gone off jars of something – anything – that I could use instead. There was nothing I could justify eating up or throwing out yet. And, I’m sorry to say, the only thing that came close was yet another jar of pickled onions sat forlorn and forgotten at the back of the fridge, left over from Christmas.

I spooned my jam, which had by now thickened to the consistency of wallpaper paste into the jars and sealed them, leaving a little in the pan for taste testing.

It’s very hard to explain what this jam was like. Texture wise, it was lumpy and a bit grainy. Not unpleasant, necessarily, but not at all refined. Taste wise, it was…weird. That’s the only way I can describe it. It was sweet – very sweet – but in a plain way. I couldn’t really taste the pineapple, other than a bit of a tropically tang on the tip of the tongue, but my husband said he definitely could, so it may depend on individual palates how much comes through.

Mostly though, it tasted of very sweet courgette and I couldn’t see when you’d eat this. On toast? In puddings? Not really – it’s not fruity or acidic enough for toast or puddings or anything that needs either of those things to cut through. With cheese and crackers, like a sweet chutney or quince jam? No – it’s far too sweet for that and not spicy enough either to add an interesting dimension. The only thing I could see this being used in because you wanted to (rather than because you had to use it up) was possibly as a filling for a lemon cake that had a lemon buttercream icing on top to provide some sourness to the relative sweet blandness. Hardly a jam for all seasons, then. Now you may want to argue that some of this disappointment was down to my lackadaisical approach to this recipe, and you may be right. But, just like an aforementioned advisor, I believe that I acted responsibly, legally and with integrity at all stages of this recipe and will therefore not be taking any real responsibility for its shortcomings.

So overall what did I learn from all this?

One – as a family, we eat too many pickled onions.

Two – Like a musical composer with a taste for philosophy and ethics dipping his unqualified toe into the world of medicine, I did not posses the skills or tools needed to make this jam a true success. I ended up losing points in almost every category, like some sort of inverse jam-based Torville and Dean (weird analogy, right?) despite this recipe not actually being that hard to pull off.

Ultimately I wouldn’t recommend you make this unless you make a lot of lemon cakes (and even then, remember, that’s an untested recipe) or you really just want to try it for yourself. The concept was interesting and in the end it wasn’t bad or inedible, it just doesn’t have a clear role in recipes. With more pineapple and less marrow, perhaps it could be more of a traditional fruity jam but as it stands this is one that I’m happy to leave in the recipe books.

E x

P.S. in the end I actually was able to think of a better mnemonic – one to perfectly combine the farces of politics and jam: Unelected Advisors Needn’t Keep To Basic W.H.O. Protocol.

Marrow and Pineapple Jam

900g of marrow when prepared

1kg of sugar

500g of drained tinned pineapple

Rind and juice of 2 lemon

You will need to sterlise 2 or 3 jars for this recipe. I recommend sterilising them while the mixture is cooking which means they will be ready by the time it’s done.

- Peel and blend the marrow to a coarse pulp.

- Cover the marrow with sugar and leave for 12 hours.

- After 12 hours, chop or blitz the pineapple finely and add to the marrow and sugar.

- Over a low heat, cook the marrow, sugar and pineapple together until the sugar has dissolved.

- Once the sugar has dissolved, bring the mixture to a boil, skimming any scum from the surface.

- When the mixture reaches 105 degrees C, remove from the heat and pour into pre sterilised jars.

You must be logged in to post a comment.