It’s another medieval one! It’s another sweet one! It’s another one where I don’t really have much idea of what it is I’m supposed to be doing!

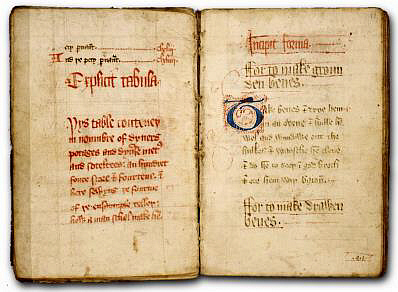

Right from the start I’m going to attribute at least half of today’s success to Dr. Christopher Monk – a man whose knowledge of medieval cuisine (particularly the cuisine in The Forme of Cury, from which this recipe is taken) is as impressive as his patience with over-enthusiastic amateurs contacting him with screen shots of recipes they don’t understand, begging for help. He could have said no. He could have done that thing where the message pops up in notifications but you ignore it forever because you don’t want to engage with such nonsense (don’t pretend you don’t know what I’m talking about – we’ve all done it. My husband’s still waiting for my response to a photo of him trying on something he called “dress shorts” in Debenhams changing room in 2017. He didn’t buy them in the end, which I guess shows that actually this approach can work sometimes.)

To put it bluntly, he could have told me to find a hobby that didn’t so often require at least some basic understanding of Middle English and other “extinct” languages. And believe me for I speak from bitter experience – knowing all the spells in Harry Potter only gets you so far with Latin. But instead he shared his translation and notes on the recipe and offered advice and encouragement. I’ve called on his expertise before and I’m sure I will again (unless he has the commonsense to block me on Twitter), so I make no apologies for the first section of this entry basically being a big thank you to Dr. Monk.

Payn Ragoun is a mystery in itself to me. Entitled “Pine Nut Candy” in Maggie Black’s The Medieval Cookbook, there is much in the original that confused me. The word “ragoun”, for example. What did it mean? Was a ragoun a style of cooking or was it a way of serving food? I wondered if it was just a word that had become lost with in time that used to mean a particular dish, like a pie, and medieval tables once groaned under the weight of strawberry ragouns and apples ragouns as well as pine nut ragouns. I decided to do a little etymological investigation, which basically meant typing “Ragoun: what does it mean?!” into Google like a madwoman until I hit on something useful. Or rather, I hit on something that just directed me right back to where I started. The University of Michigan Library’s online Middle English Compendium (yep, that’s a thing) had this explanation for the word “ragoun”:

“The name of a dish made with honey, sugar and bread.”

The associated quotations took me directly back to the recipe I was looking at, which didn’t do too much to clarify what this dish was meant to be. The compendium told me that the word “ragoun” possibly came from the Old French word “regon” meaning a mixture of wheat and rye. So, though I still felt a little nonplussed by what a ragoun was supposed to actually look like, my confidence levels rose as I turned to my husband, who hadn’t asked at all, and triumphantly exclaimed “well, at least I know it’s got bread in it.”

Reader, it did not contain bread. Let me explain…

The second thing that had confused me was the word “thriddendele” in the translation of the recipe I had. Maggie Black had explained this was a “mystery ingredient” (she translated the word “thriddendele” as meaning an anonymous “third item”) which she had taken to mean breadcrumbs. This seemed completely logical and fit in with my tenuous understanding of “ragoun” and the word “payn” in the dish’s title (meaning bread, from the French pain.) But this was where my lack of understanding of Middle English – and to be honest, modern English – came in handy. I had misread Maggie Black’s entry and thought she had meant that the word “thriddendele” was the word for the mystery ingredient itself. I wasn’t happy with my lack of knowledge of this ingredient – if it was going to be the third item in this dish I damn well wanted to know for sure what it was. And so, with all the puffed up indignation of a woman who has no idea what she’s doing but already spent money on most of the ingredients, I messaged Dr. Monk for help.

Firstly, he clarified, the dish seemed to be a type of soft toffee with pine nuts and ginger mixed in. There was a reference in the recipe to “take up a drop thereof with thy finger and put it in a little water and look if it hangs together” which indicated a method similar to the confectioner’s technique of checking when sugar has reached the “soft ball” stage for fudge.

Secondly, “thriddendele” wasn’t the name of an ingredient in its own right (as Maggie Black had also pointed out but I’d been too dense to realise) – it was from an Old English word meaning “third deal” as in part or portion. The instructions in my book may have translated “thriddendele” as an instruction to add breadcrumbs as the third part of the recipe because of how the original sentence was structured: “add thereto pine[nuts] the thriddendele (third part) & powdour gyngeuer.” However, word order wasn’t fixed in Old English, like it is today (this is also the case in Latin; Wand, Accio! would work just as well as Accio, Wand! by the way. As would Leviosa Wingardium, it just sounds a bit rubbish and means Hermione couldn’t do the special voice.) The shifting word order means that though the recipe was written “add thereto pine[nuts] the thriddendele (third part)” it could just as well read “add thereto the thriddendele (third part) pine[nuts].” Which actually makes much more sense as a cook – especially when you fall down the etymological rabbit hole and see that “thriddendele” can also mean one third of a whole – meaning, in this case, the word “thriddendele” sort of acts as two instructions; to add a final third ingredient (pine nuts) in a particular quantity (equal thirds to honey and sugar.)

The absence of bread and presence of pine nuts as the “thriddendele” becomes even more compelling after a quick analysis of modern understandings of the word “bread” versus medieval understandings of the word “bread”. To go back to the Middle English compendium, the word “payn” could mean a literal loaf of bread as we would recognise it today. But there was a secondary use of “payn” which just meant something of a breadlike consistency, such as pastry. Even more interestingly – that wasn’t a yawn, was it? – the compendium links this “breadlike consistency” use of the word “payn” back to the word “ragoun” as an example of a dish that matches this description. Payn Ragoun therefore wasn’t a dish made with bread; it was a dish that mimicked the consistency of bread, or bread dough.

I though this was meant to be a food blog, not an English blog?

Right. And before we move on – if there are any academics out there, or even just anyone who knows their stuff about words and… well, stuff, I guess, and thinks I’ve gone off on a huge incorrect tangent in my non-academic analysis, please let me know (nicely!) and I’ll correct it. If I can be bothered, that is, and if I can do it in a way that makes me look like I’ve grown to have the intellectual prowess of both Stephens combined (Hawking and Fry, FYI).

So, I knew I was working with equal parts honey, sugar and pine nuts. The question was how much was equal? “Thriddendele” could often mean one third of a gallon, which was about 1.5l. This was an obviously unacceptable amount for anybody who valued not having cavities in their teeth, so I scaled it down a bit and decided to switch to measurements in grams rather than ml which made everything a lot simpler.

I melted 250g of honey with 250g of sugar. This bit caused me some problems too, if I’m honest, as the recipe called for “Cyprus sugar”. This was the best quality available at the time, made in Cyprus, which had a thriving sugar industry during the 14th and 15th centuries and was considered the cream of the crop in England thanks to the many stages the cane went though to extract the molasses. The Forme of Cury was written by Richard II’s master cooks and though it was intended to be used as an instructional book for everyday dishes, it was also supposed to show off the king’s fabulous wealth and the skill of his cooks. Dishes such as “common pottages” were all well and good for the merely well off, but any dish requiring one third of a gallon of Cyprus sugar was firmly in the realm of the rich, thank you very much.

I was faced with a problem: did I stay true to the taste of the recipe – even if that meant using a non-regal unrefined sugar in an effort match the levels of refinement at the time – or did I try to copy the intent of the recipe and use the most highly processed white sugar I could? In the end I settled for an unrefined golden sugar made from 100% cane (not sugar beet). In all honesty, it was pretty much all the Co-op had on the shelf anyway, other than a packet of “Schwartz Hot Chilli Con Carne Mix” which I’m fairly sure had just been put in the wrong place.

Sugar and honey bubbling away, it was soon time to test the mixture. The author of the recipe had, presumably, a very dark sense of humour and advised dipping a finger into the seething mix of melted sugar to “take up a drop…in a little water” and see if it held its shape. I can imagine him laughing wickedly at the idea of trainee cooks taking his advice and screeching in pain as their flesh melded with molten syrup. In case you want to recreate this recipe yourself and it’s not obvious enough: do not touch boiling sugar with your fingers. Or hands. Or, (and I really shouldn’t have to spell this out), any part of your body at all, you absolute weirdo. I used a sugar thermometer – not technically authentic but far more likely not to land me in A&E and continued to boil the honey and sugar together until it reached the “soft ball” stage and registered 112 degrees C. I was a bit put out not to reach the vastly more amusing “soft crack” and “hard crack” stage but I think Richard II’s cooks were less immature than I am.

Once I’d reached the correct temperature, 250g of pinenuts were added, along with a good pinch of ginger, and stirred in. (I’m aware that is a hugely expensive amount and the fact I used a mixture of pine nuts from old open bags we had in already and a bag of specially bought ones might have skewed my perception on the overall cost of this dish, but it would still work with any similar cheaper hard nut.) The whole mixture was poured out onto a greaseproof paper lined baking tin and allowed to cool for a few hours.

The author of the recipe suggested serving this alongside “fryed meat, on flessh days or on fisshe days”, showing the medieval tradition of serving sweet foods alongside savoury, but we just decided to cut it into fudge like rectangles and eat it as it was instead.

My first thought were that it wasn’t as sweet as I’d expected. Obviously it was sweet, but it wasn’t that tooth-aching sweet you can get from fudge. It was quite woody because of the pine nuts, and very mellow. A bit like nougat is, but less smooth. The ginger was warm rather than overpowering and spicy, which worked really well. However, my results will be different from any others because a lot of the actual flavour came from the honey, which is dependent on local flowers and the nectar the bees use. Using a locally produced honey, my Payn Ragoun wasn’t overly floral or perfumed, but I can imagine that certain honeys would yield different results. Thyme honey, for example, would have a much stronger aromatic flavour.

I also think I should have cooked it for slightly longer. It held its shape when cut into rectangles, but in an oozy way. It would only take a hot afternoon to transform this back into liquid stickiness so cooking it to a “firm ball” stage (118-120 degrees C) might help a little more with that.

In fact, I was sure this would be brilliant as a brittle. The instructions were vague at best about how long the mixture should boil for and, though the reference to testing a ball of mixture in water seems to correlate to the soft ball stage, there’s nothing to indicate it had to be that. It’s not outside of the realms of possibility that a cook got distracted (or had to go and plunge his hand into a bucket of cold water after trying the medieval soft ball method) and let the mixture bubble a bit longer. Furthermore, some of the recipes in Forme of Cury are similar to those found in the 14th century French/Italian cookbook Liber de Coquina, which had links to Arabic cooking. Why does that matter? Because centuries earlier Arabic cooks had been busy experimenting with sugar and were among the first to develop hard candy. By the 12th century there were clear signs of hard candy in some European recipes. While hard candy might not have been common in England by 1390, surely it would have been something the cooks of Richard II, who must have been reading other contemporary Arabic influenced works such as Liber de Coquina, would have known about? So I saved a bit of the mixture over and let it cook longer – to the hard crack (teehee) stage.

As expected, the brittle version of Payn Ragoun was even better than the fudge version. I love brittle, so didn’t mind that I was still chewing on a small piece of it two hours after I’d started, or that with each bite I could feel my teeth loosening from my gums. The brittle version seemed less sugary but more honeyed than the fudge version too, so if you prefer less sweet sweets, let your mixture boil for longer.

Overall, this was a great sweet treat to make. It was surprisingly quick and easy to rustle up, if you don’t panic over melted sugar, and tasted very, very good. If you have honey and sugar in you should definitely try this – add pine nuts for a medieval version or experiment with other nuts – hazelnuts were used in medieval England too – or bits of fruit added at the last minute (just avoid super soft fruits like banana – though why would you add banana to anything anyway?!). I could even see a slab of this plain with flakes of sea salt scattered over the top of it as it cools working well too. I’d recommend the brittle version over the fudge, but it’s so easy to make you could just do two versions anyway.

Enjoy. And please, for the love of God, don’t stick your fingers in melted sugar. Just… don’t.

E x

Payn Ragoun

250g honey

250g golden caster sugar

250g pine nuts (or a combination of similar hard nuts such as almond

Pinch of ground ginger

- Line a small baking tray (I chose 28cm x 18cm) with greaseproof paper.

- Measure out all the ingredients before you start.

- Heat the honey and sugar in a pan over a low flame, swirling it occasionally to stop it clumping. Using a thermometer, or the cold water test, cook the sugar to 118 degrees C. If you want to make brittle keep cooking it until a thermometer reaches 146-1154 degrees C.

- When the sugar has reached the right temperature, take it off the heat and stir the pine nuts and ginger in until fully mixed. You will want to be a bit quick in doing this to stop the sugar and honey solidifying too soon.

- Pour the honey, sugar and pine nut mixture into the lined baking tray and leave to set somewhere cool, like a cupboard (not a fridge).

- After it is set, cut it into chunks with a sharp knife and enjoy. You should store it in greaseproof paper in an airtight container for lasting freshness.

Delicious! I have got to try this now.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, do! I think the brittle is better than the fudge, but both are good.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This sounds amazing and the modern craze for a salt/sweet taste realy would work.

LikeLike

I can absolutely see it working! In fact, pretty much anything on top of this would work. It’s like chocolate bark but with honey instead.

LikeLike